Pressure on hospitals ‘at a really dangerous point’

Getty Images

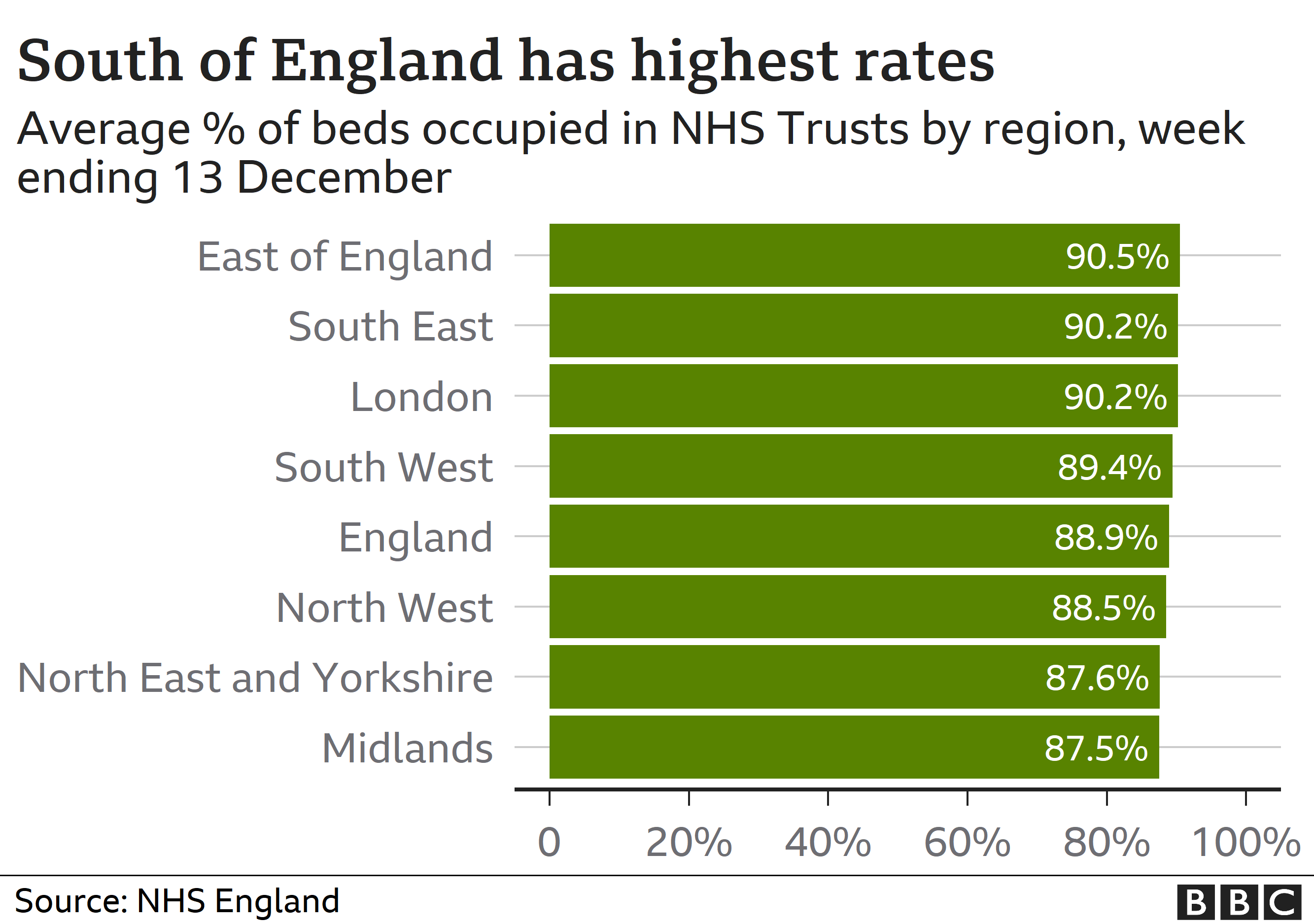

Nearly 90% of hospital beds in England are full as hospitals try to cope with the demands of Covid in addition to normal winter pressures.

Ambulances queuing to offload patients, staff sickness and a lack of beds mean hospitals are “at a really dangerous point”, say emergency doctors.

This could result in some trusts facing the decision to stop non-Covid work.

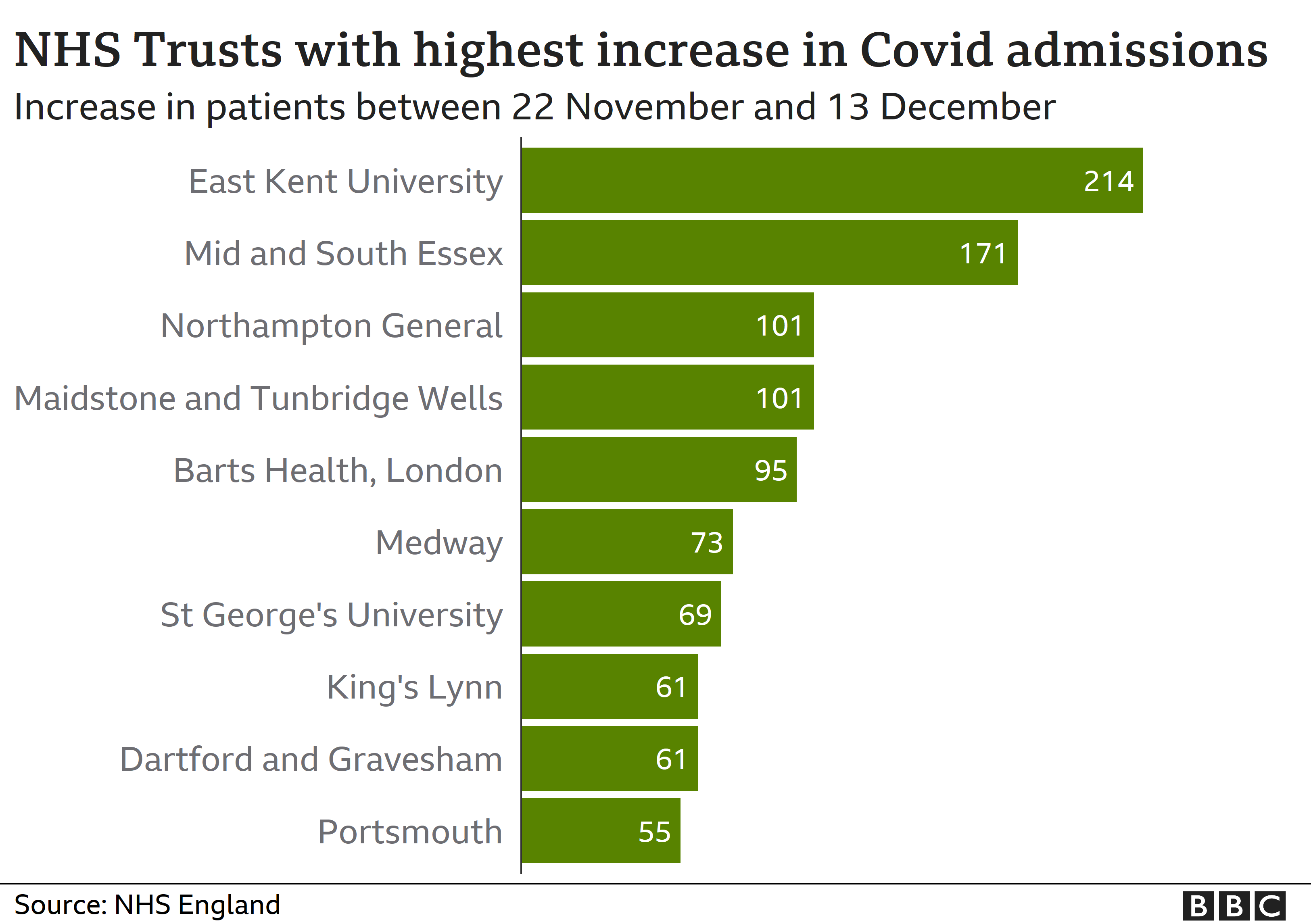

Rises in hospital admissions are particularly affecting areas in the south.

How are hospitals managing?

The percentage of NHS hospital beds which are occupied is increasing and has reached almost 89% in England for the week ending December 13.

This is the highest occupancy rate so far this year – it’s still lower than the same time last year, although the extra burden of Covid is likely to make hospitals feel they are much busier.

A safe level for bed occupancy is below 90% but nearly half of NHS trusts report a figure currently higher than this – the largest proportion this season.

The south and east of England are facing the most pressure on beds.

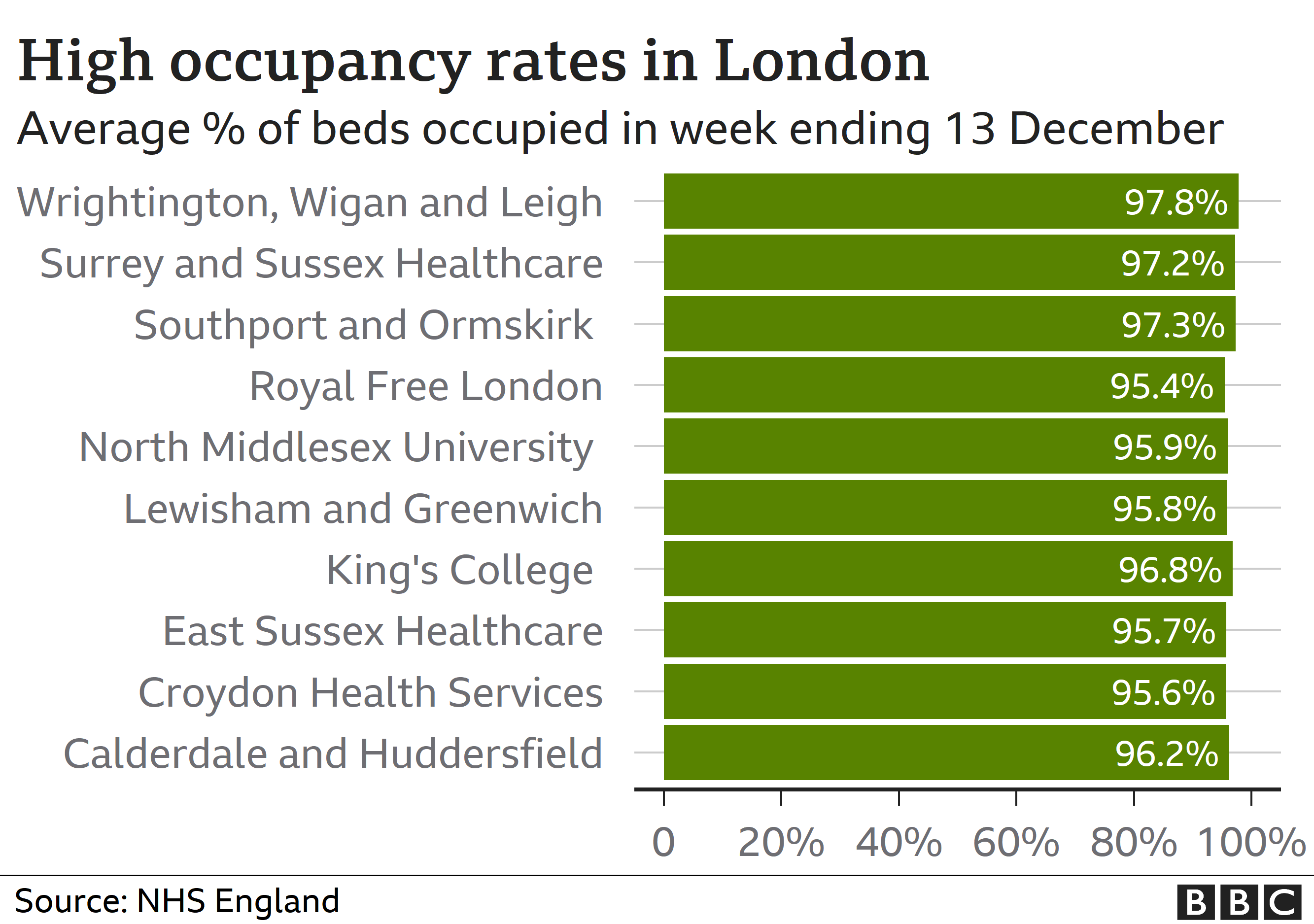

Across England, individual hospitals and trusts are coping with varying levels of pressure, and these can change daily.

Trusts in and around London make up most of the busiest ranked by beds occupied – all of the top 10 are over 95%, with three running even higher at over 97%.

Dr Katherine Henderson, president of the Royal College of Emergency Medicine, told the BBC: “We are at a really dangerous point which could tip into finding it incredibly difficult to manage.”

She said the combination of staff who are tired, unwell or having to isolate, and the additional burden of Covid, was an “awful situation” to be in.

She added that it would be difficult to keep other work going, with pressure “so tight” on intensive care beds.

“We have to get a grip of the virus and do whatever it takes,” Dr Henderson added.

Recent rises in numbers of people admitted to hospital with Covid are putting major pressure on other hospital work.

For example,

Leicester’s hospitals are now on the highest level of alert while three in Essex have stopped non-urgent operations due to the number of Covid-19 cases.

It also means critical care is getting busier in England, with three-quarters of of adult critical care beds occupied last week – up slightly from the previous week.

However, this figure was higher during the week ending 22 November in the midst of the second lockdown, when it hit 76.4%.

Three NHS trusts reported their critical-care beds were 100% full – Calderdale and Huddersfield, Portsmouth Hospitals University and Sandwell and West Birmingham, in the week to 13 December.

What about ambulance delays?

Delays in ambulances transferring patients over to emergency staff when they arrive at hospital are also causing knock-on problems.

One in seven ambulances faced delays of 30 minutes doing this, affecting more than 13,000 patients. The target is to transfer patients within 15 minutes.

The highest proportion of ambulance delays occurred in University Hospitals Plymouth NHS Trust (43%), Royal United Hospitals Bath NHS Foundation Trust (42%) and North West Anglia NHS Foundation Trust (41%).

However, ambulance delays are common during winter and this number is not particularly high for this time of year.

How does coronavirus affect NHS staffing?

By BBC Reality Check

Like most front-line sectors, coronavirus has had an impact on staffing due to illness and self-isolation.

Back in April, when the virus first peaked, the staff absence rate reached 6.2% – the highest on record. This means that more than one in 20 working days were lost to illness.

Roughly a third of these were lost due to coronavirus.

We don’t have data coinciding with the most recent surge in cases , so we can’t assess how well Kent and Medway – which is very much at the epicentre of the outbreak at the moment – is dealing with staffing. But when London was the centre of the crisis, sickness rates hit as high as 7.2%.

With winter coming in, the pressures of coronavirus will add to what is already a difficult time of the year for staffing; over the past five years, January’s absence rate has averaged at just under 5%.

NHS Providers has pointed out that this is combined with already high staff vacancies, which stand at 85,000 in England. This is down from 110,000 in 2018.

It is also worth mentioning that – with the exception of April – coronavirus has not been the leading cause of staff absences throughout the year. Burn-out, anxiety and other mental health issues equate to one in three sick days for NHS staff in most months.

Published at Fri, 18 Dec 2020 15:50:28 +0000

Comments

Loading…