‘Price rises likely’ due to global shipping mayhem

Getty Images

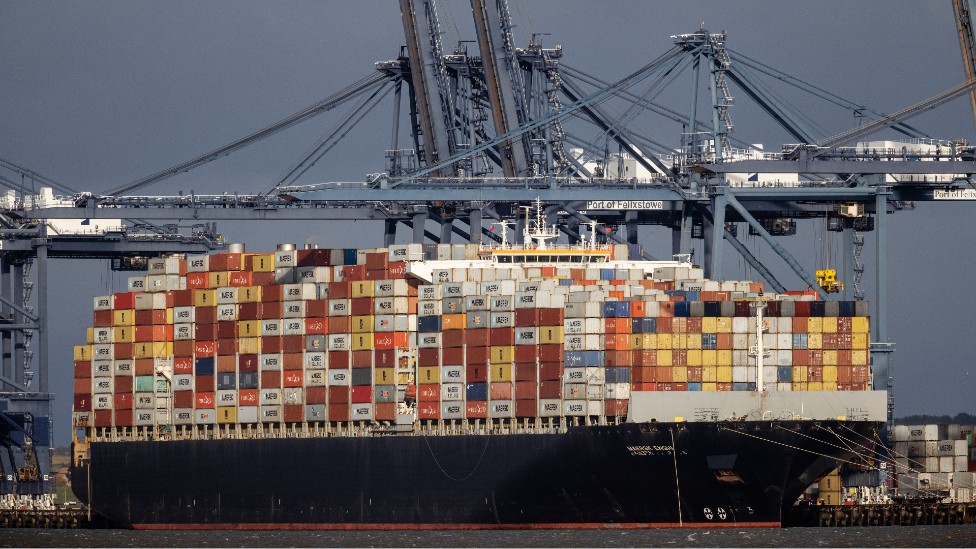

Businesses say a global shipping crisis is causing freight costs to soar and UK consumers may soon see price rises for imported goods.

On top of skyrocketing shipping rates, carriers are adding congestion charges for imports to Felixstowe and Southampton, because of severe delays.

The logistics industry has written to the Department for Transport calling for it to help clear port backlogs.

One freight director told the BBC the UK’s ports are currently “broken”.

Global shipping schedules were initially disrupted during the early stages of the pandemic, but recently a surge in demand for imports and a backlog of empty shipping containers are causing bottlenecks at UK ports.

Adam Russell, who imports home appliances such as heaters and air conditioners for One Retail Group based in London, said the situation is “scary”.

“I’ve always been able to find a way to keep the business moving, but if I can’t find a way to move the goods into the country, then that’s when the business stops,” he said.

“We used to pay $2,000 to ship a 40-ft container to the UK, now we’re paying at least $8,000 up to $10,000.

“Ultimately that means we’re going to have to stop importing or we’re going to have to pass that on to the consumer.”

He said it’s “near impossible” to get goods out of China now because fewer vessels than normal are sailing to the UK and there’s also a shortage of empty containers ready to be filled in Chinese ports.

Major shipping companies including Marseille-based CMA-CGM have told UK importers no more bookings can be made for ships sailing from Asia until the last week of December.

The

Japanese carmaker Honda said delays at UK ports are holding up imports of parts and production will temporarily cease at its Swindon plant from Wednesday.

The Builders Merchants Federation has also complained of delays for building supplies such as screws and timber, crucial for building new homes.

Flexibility call

Organisations representing the UK’s ports, shipping and logistics sectors have written to Transport Secretary Grant Shapps, urging the government to do what it can to improve the situation.

“We recognise government’s capacity to step in is limited, but where they can, they should look at ways of increasing the capacity for moving containers on and off ports,” said Tim Morris, chief executive of ports’ trade association, the UK Major Ports Group.

“That could mean running more and longer trains to and from ports, allowing hauliers more flexibility to collect containers out of normal hours, and for drivers to take on longer shifts where that can be done safely,” he said.

The letter to the Transport Secretary also warns the government about further potential disruption when the Brexit transition period ends in January.

The Department for Transport said partners across government are working closely with the freight industry to resolve the challenges in the global container system.

‘Extremely stressful’

Logistics firms which are responsible for transporting goods from ports to warehouses say the situation is creating huge amounts of stress.

“It’s pretty dire if I’m honest,” said Ryan Clark, director of the Essex-based freight forwarder Westbound Logistics Services.

“At the moment, we’re having an extremely stressful time, to say the least. We’ve had one staff member leave because she can’t take the customers’ complaints.”

“But we are all in the same boat. We are trying to get people’s goods and products into the UK but the shipping rates are changing daily and we’re having to update customers and give them the bad news.”

Mr Clark said that as shipping orders into the UK have surged, the unloading time for vessels has increased.

That means there are fewer berthing slots available at ports and congestion problems are getting worse.

Problems that have been plaguing Felixstowe for weeks have now spread to Southampton and the system is “broken”, he said.

“The increase in freight is either creating more expensive prices for the consumer, or unsustainability for businesses that will be forced to close where the onward price cannot be increased.”

He also said poorly performing ports mean the UK risks becoming a “feeder” island, rather than a direct port of call for shipping firms, leaving importers with the added cost of transporting their cargo from continental ports such as Rotterdam or Antwerp.

A spokesperson for DP World in the UK, which operates Southampton port, said: “We have made clear that we are currently dealing with higher than usual yard volumes and also bad weather, including fog, leading to our truck turnaround times being longer.

“We expect levels to return to normal over the next week.”

‘We’ve got to put prices up’

But Ben Charlton, a business manager for paving importer Hanson Stone, based in Mansfield, said logistics firms are telling him it will be two to three months before the situation returns to normal.

He said he’s been waiting since the start of the month for containers to be unloaded at Felixstowe, but he’s been told it could be another three weeks till they arrive.

“We’re a start-up company, we’ve only been running a year, we’ve had Covid to contend with, and now we’ve got this,” he said.

“We’re paying about £1,200 more per container in increased shipping costs, plus a £25 surcharge for port congestion.”

That surcharge adds up, Mr Charlton said: “We do 150 containers so that’s about £3,750 plus VAT.

“Ultimately it’s [all] going to get passed on to the end consumer and landscaping companies who buy from us down the line.”

Mr Charlton said the company operates on a credit system, where suppliers in India are paid 30-60 days after the stock arrives in the UK but the delays at Felixstowe are making cash flow a real problem.

“We’re having to pay suppliers up front for stock that we haven’t even seen,” he said. “We’ve got to put prices up, it’s a last resort.”

Credit crunch

Eleanor Hadland, a ports analyst at the maritime consultancy Drewry, said “the whole global container supply chain is basically out of balance”.

The system stopped working properly when economies in various parts of the world shut down and re-opened at different times, as they dealt with Covid-19.

That led to shipping firms falling behind when it came to picking up empty containers at ports and taking then back to Asia.

Now, with import demand surging again in Europe and North America, shipping lines are choosing to allocate space on vessels to companies that are exporting goods, since that’s more profitable than picking up empty containers.

And that causes more and more empties to clog up UK ports as well as a container shortage – and more delays – in China.

She warned the end result could resemble the credit crunch of 2008 when importers’ lines of credit dried up.

“If the time it takes to receive goods at your shop is lengthening, you’re having to find the cash to pay your suppliers sooner,” she said, and that could have huge ramifications for global trade.

“What we’re seeing is a trend away from globalised supply chains and people looking to buy goods regionally,” she said.

Published at Wed, 09 Dec 2020 00:02:02 +0000

Comments

Loading…