Catching up with former Enquirer food writer Polly Campbell – Cincinnati.com

| Cincinnati Enquirer

It’s been more than six months since longtime food critic and writer Polly Campbell penned her farewell column in the pages of The Enquirer. Given the emails I’ve received, I know she is missed. Given the fact that I overheard two men referring to me as “the new Polly” the other day, I know that her presence still looms large. So what has the “original Polly” been up to since June? As a special Christmas present to readers, my plan was to go out to eat with her. Maybe try a new restaurant. Maybe do a joint review. Unfortunately, the same virus that arrived at the end of her tenure here and at the beginning of mine is still very much with us. So we did what we all do these days. We settled down at our desks and talked via Zoom.

What she’s been up to

Polly told me she spent her first months of retirement hiking, walking in the woods and, well, eating a lot of salads. “It’s been strange,” Polly told me. “Because of COVID, retirement is not what I thought it would be. No trips or volunteering or any of the things I figured I could do. I have been able to be healthier. For the first time in 23-and-a-half years, I’m completely in charge of my own food landscape, which is the only way to really do this since, as you probably know by now, it’s pretty hard to eat just one french fry.”

Her “diet,” though she loathes the word, involves eliminating carbs as much as possible, but she promises she’ll never write anything about dieting. “I don’t think anyone should ever write a story about losing weight because, inevitably, that person will always gain it back.” That said, Polly has no regrets about sharing her struggles with Type 2 diabetes with readers back in 2017. “I managed to lose weight and get in shape while I was still working at the Enquirer, and it was kind of amazing,” she said. “It’s an article that a lot of readers responded to because, well, a lot of people have Type 2 diabetes.”

She’s also grown obsessive about food waste, keeping a careful eye on her fridge, freezer and pantry at all times. “I keep making lists of what we have and what we still need to use up,” she said. “I ask myself how I can use that last two inches of jarred chili sauce and not throw it out. I just shopped this morning for the rest of the month. I enjoy that household food economy, figuring out in advance what to eat all week, and how to use old recipes to use up ingredients.”

Last month, Polly published an excellent book called “Cincinnati Food: A History of Queen City Cuisine,” a book two years in the making (during which she took quite a few vacation days to finish). A book that I will keep on my desk as a reference tool for years to come. “I don’t think I could have lived with myself if I’d never written a book,” she said. “I thought about doing a Cincinnati cookbook, but then I realized how hard it would be to collect all of those recipes and get them right. I thought maybe I could write about the things that make Cincinnati food what it is, and the history behind what we eat here.”

Many of the articles are based on her two-plus decades working for The Enquirer. Her goal was to create a survey of our most cherished food traditions, especially since she’s known for a long time that many people who live here are unaware of origins of things as common as Cincinnati chili or goetta, foods, she says, that we should embrace and be proud of. “We don’t want to eat the same foods everyone else does. We want something that’s our own. We need those little points of pride.”

What she misses

While COVID-19 has turned restaurant grand openings into bittersweet affairs, Polly misses the days when she kept a running list of all the new places she needed to try. “I enjoyed knowing about new things,” she said. “Every time we were driving around, I would look out the window to see what was new. I was at Hyde Park Plaza the other day, and I wondered if there was anything new there. I thought, ‘I should go to the Milk Jar [a new Thai ice cream and bubble tea cafe] and try something.’ Then I thought, ‘Polly you don’t have to do that anymore,’ even though I wanted to!”

She also misses just talking to people in the food community about their new ideas. “There are so many people here who are really creative and come up with cool stuff. When I started the job, a lot of people were just doing the things they thought would work. But as time went on, and Cincinnatians started getting really into the food they were eating, there were more and more possibilities for [the local food and beverage industry] to get creative.”

One of her favorite examples is Katie McDonald, owner and winemaker of Skeleton Root Winery in Over-the-Rhine, and her decision to reintroduce the Catawba wines that Nicholas Longworth made back in the 1850s (back then, Cincinnati was sort of the Napa Valley of the Midwest, according to Polly). “When she told me about it, I thought it was the coolest thing I’d ever heard – and it turned out to be delicious.”

She was also impressed with Renee Koerner, owner of Big Fish Farms. “Who else would think this was a good place to raise paddlefish and make caviar out of it?” Polly asked. “I miss stumbling on those things; the things I found out about by just talking to the people around me.”

One thing she doesn’t miss is giving personal restaurant recommendations to strangers. “I never liked giving them,” she said. “When people ask, ‘Hey, where should I take my mom this weekend?,’ I think, ‘Well, I don’t know you, and I don’t know your mom, so I don’t really know what she might or might not like.’ And sometimes my mind just goes blank, and I can’t even think of the name of the restaurant I would recommend anyway.”

Jeff Ruby reviews Enquirer restaurant critic Polly Campbell

Jeff Ruby, noted Cincinnati restaurant mogul and entrepreneur, flips the script on longtime restaurant reviewer Polly Campbell.

Cincinnati Enquirer

How things changed while she was here

Polly started working at The Enquirer in 1996; a time when white tablecloth restaurants, – most notably the Maisonette, as well as not-so-nationally known spots as the Celestial – were still very much revered (even among those of us who could never afford them). The clientele of such places skewed slightly older, and slightly richer.

But it was the kicked-back casualness of neighborhood joints such as Zip’s Cafe, Arthur’s, Skyline and LaRosa’s, as well as our dedication to our local bakeries and butchers that struck Polly the most. While the rest of the country seemed to veer toward chains, “Cincinnati hung on to certain things to eat that were unique to this city,” she writes in her book. “Regional foods were dying everywhere, but our population held onto certain foods and brands that were eaten here as a matter of habit – unremarked on and not marketed to the rest of the world. We went to neighborhood butchers and bakers, ate our German-inspired meats and drank our local beer.”

Then came the revitalization of OTR.

“The OTR thing was so much fun,” she said. “Those restaurants felt the way going to a restaurant in San Francisco or Chicago did. There was this excitement about them; the sense of getting there and being seated. There were all of these young people there. When I went to a restaurant, I would bring the average age of the room down, but now all kinds of people are going down there.” Reviewing these new restaurants proved challenging to Polly, who said evaluating a high-end place like Orchids or Boca came far more naturally to her than it did for places that specialized in hot dogs or fried chicken.

“It was a new style of dining and everything was casual,” she said. “When the Eagle opened, I loved it, even though all they did was fried chicken. The food was carefully done and delicious, but it was so focused. I asked myself: ‘How do you compare that, in star ratings, to a place like Embers that does a lot of different things?’ I always had to make sure [my reviews] aligned with people’s expectations of what the restaurant would be like.”

Critic to critic

During our conversation, Polly and I talked a lot about how about how the job as food critic has changed over the years. Though I’ve been writing about food for at least 20 years, I’ve never served as a critic per se. No elaborate disguises in my past; no hosts sweating my arrival when he or she sees an outdated photo of my ugly mug Scotch taped above the hostess stand. While Polly’s title was once Food Critic, mine is Food and Dining Writer. And while Polly tried to maintain a certain distance with local chefs, I came into the job considering many of them friends, though I don’t let that get in the way in terms of coverage.

“The role critics play has changed so much,” Polly said. “It used to be like it was a contest and you were the judge. All [the chefs] had to submit to your judgement because you knew what you were talking about. But when I was a critic, and I gave up being anonymous, I wanted people to know I wasn’t doing a white glove test. I wasn’t there to make sure you were living up to my ideals. It was more like, I went to a restaurant and figured out what they were trying to do and, based on what I know about food, whether they actually pulled it off.”

For much of her career, Polly tried to remain anonymous. Many of you, I’m sure, remember the famous hat she wore whenever her photo appeared in the paper. But in 2016, she lost the hat, realizing that the relatively small size of this city, and the internet, made remaining anonymous almost impossible. Still, the loss of her anonymity made her job more complicated in terms of the boundaries she drew between herself and the restaurant community.

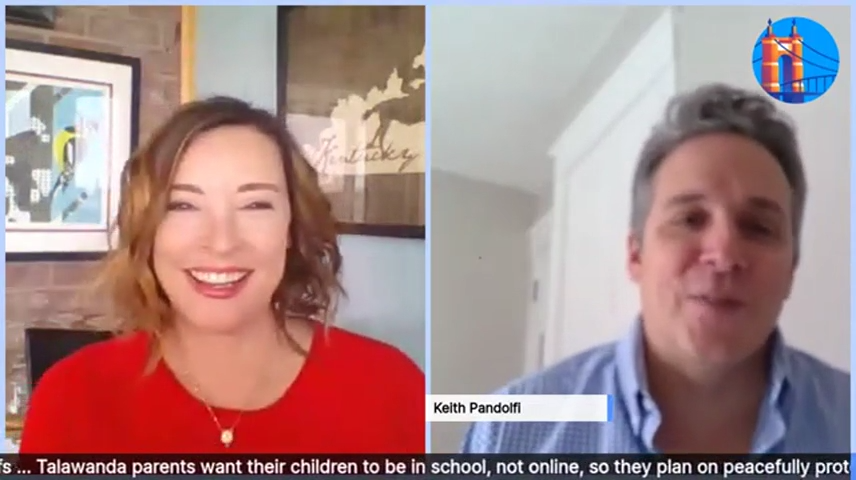

Kathrine Nero introduces Enquirer’s new food and dining reporter Keith Pandolfi

Kathrine Nero chats all things culinary in Cincinnati with Enquirer’s new food and dining reporter Keith Pandolfi.

Kathrine Nero, Cincinnati Enquirer

“I didn’t try to be anyone’s friend,” she said. “I didn’t want that.” But there were certain chefs she admired so much that she managed to develop relationships at a safe enough distance to maintain her objectivity. And it wasn’t unheard of for them to provide her with ideas for her next column

“I always loved talking to Jean-Robert de Cavel,” she said “I got a lot of my information from him, and would always end our conversations with, ‘So, have you heard anything good lately?’ ” She loved her talks with Joe Lanni, co-owner of the Thunderdome Restaurant Group, who taught her just because a restaurateur was interested in growth didn’t mean he or she would stand for sacrificing quality. “Joe was so great at articulating what they were trying to do,” said Polly. “I had to start wondering why all of their restaurants were so good.”

She also has an affinity for Elias Leisring, owner of Eli’s BBQ (“his sentences were always completely thought out before he said them out loud”), Japp’s owner Molly Wellmann (“she’s such a source of joy and fun; I just love her”), Jean-Francois Flechet, owner of Taste of Belgium (“a great source who always called you back”), as well as Jeff Ruby and his daughter Britney Ruby Miller (“it’s amazing what she’s stepped up and done”).

COVID-19 had already ravaged the restaurant industry when Polly retired this summer. And it’s something that’s still hard for her to watch, even from the sidelines. “I knew it was going to be a terrible thing, and I can’t talk about it without getting kind of political. I just think the goal of the government should’ve been to come out of this with the fewest people dead, and the fewest number of small businesses, including restaurants and bars, gone.”

She said the efforts the government did make simply weren’t enough. “The PPP loans were so confusing. They were aimed at getting people back to work when there was no work, or people shouldn’t have been going back to work. If they had just supported the restaurants themselves one way or another, they could have accomplished both goals, keeping both people and restaurants from dying.”

When I asked her for some advice on covering such an unprecedented event, she told me one of the most important things was to tell the stories of these restaurants; to make the experiences they’re having relatable.

As far as how to do my job once this is all over? Her primary advice was to simply remain humble, and not EVER be mean spirited, a lesson she conveyed to me via a cautionary tale about one the first reviews she wrote for The Enquirer. The place was located in a suburb that shall remain nameless. Polly didn’t like the food all that much, so instead of trashing it, she poked fun at the suburb, the name of the street on which the restaurant was located, the atmosphere of the place itself. “Since I didn’t want to talk about the food, I thought, ‘I’m just going to have some fun and amuse myself a little.’ “

She realized her mistake when, the week the review ran, the owner of the restaurant called to tell her that he’d taken out a second mortgage on his house to open the place. “I realized that you don’t make fun of places; you don’t use them as an opportunity to make stupid jokes. That it’s just so disrespectful to do that.”

She also told me to keep my mind open. To drive out to the suburbs and the small towns surrounding Cincinnati as much as possible. To sit down with a book or a newspaper and pay attention to how and why people love a place. “You have to respect that people will always love something you don’t think is that great,” she told me. “You can’t be a snob. She recommended that, once the pandemic is over, I talk to community groups, to church groups and Kiwanis groups, to make sure I create a real connection to the community.

As we wrapped up our conversation, I realized why so many people in this city still have a hard time saying goodbye to Polly Campbell. And why, until I prove myself and make the sorts of connections she once did, I’ll have to settle for being “the new Polly” for quite some time.

Published at Thu, 24 Dec 2020 02:56:41 +0000

Comments

Loading…