Food Books To Feed The Soul – Forbes

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

Take five: Books that explore food and food culture

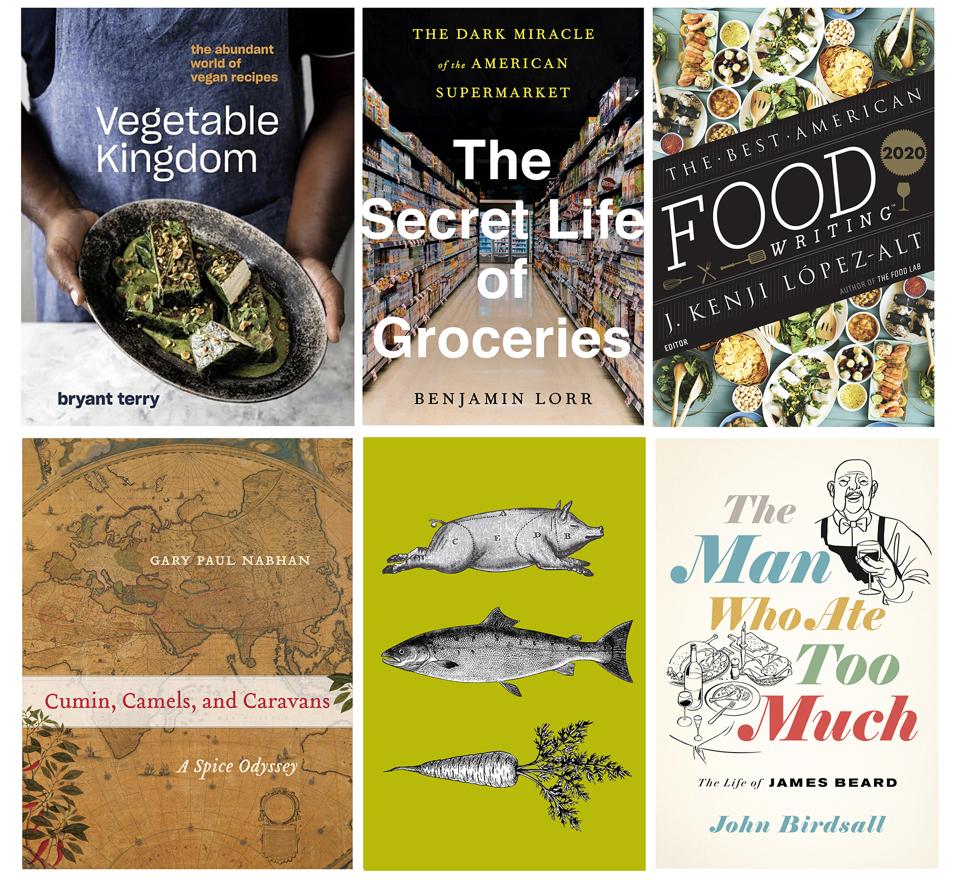

Courtesy of publishers; collage: LBortolot

So, after all the dystopian novels and pandemic literature, what did y’all read this year? My list reflected what most concerned me (and probably most people) in 2020: health, food and travel. While I wasn’t aiming for a theme, these books made their way onto my desk because in some way, they all address a topic of conversation this year.

One book that captures so much of this year is “Vegetable Kingdom,” a collection of globally inspired recipes by chef/activist Bryant Terry. This is a great book to consider in a year when citizens marched for social justice, an unprecedented number of people lined up for food assistance while the food industry suffered a collapse all through its supply and distribution chains. Food activism in the industry, of course, is not new, and has many vocal chef champions such as Dan Barber and José Andrés. My sense is that Terry is more of a quiet screamer—just as passionate but seeks another way in—food and social justice through elevating and de-cliché-ing Black culinary traditions (how to “Blackify” fennel is the opener of his cookbook and the subject of a New Yorker podcast).

Terry is chef-in-residence at the Museum of the African Diaspora in San Francisco, with programming based on the intersection of food, farming, health, activism, art, culture and the African Diaspora, and a lot of this is reflected in this book. And while that sounds like a heavy platform, the recipes are thoughtful, approachable and don’t require access to epicurean stores (there’s a helpful list of cupboard requirements). I like how the book is organized by topics such as roots, stems, bulbs and tubers, giving me a quick scan for meal planning, but it also places plant-based foods as the star of, not an after-thought on the table. The book is also a pleasure to hold: neither heavy nor cumbersome in size, with stunning photography on quality matte paper [10 Speed Press].

With food sourcing newly on my mind, I reread a couple of Michael Pollan’s books, but a new book caught my eye, The Secret Life of Groceries by Benjamin Lorr, an investigative writer whose previously reported on the yoga industry. I’d been thinking about the underbelly of the industry since reading a New York magazine story a decade ago on the ethics of food sourcing, sadly coming around to the idea that even when I think I’m doing good, I’m probably not. But seeing grocery store employees become our new essential workers during an unrelenting pandemic, I rethought not only what I bought for my personal consumption, but how my purchases contribute to someone’s safety, on-the-job comfort and well-being. If nothing else brings you to consider the same, read Lorr’s opening description of cleaning the fish counters at Whole Foods. It brought to mind Sinclair Upton’ 1906 The Jungle, a semi-reported novel detailing the unethical treatment of meat-packing workers, and demonstrating that the more things change, the more they stay the same. Lorr empathizes with workers who are the silent gears of the machinery (he either accompanied or worked alongside them for boots-on-the-ground insights), questions how consumers use food as a vehicle for ethical responsibility and suggests we’re really all pawns in the big food game. It’s not subtitled, “the Dark Miracle of the American Supermarket” for nothing. In the end, you’ll think twice about reaching for that cheap carton of oat milk at Trader Joe’s: somewhere, someone paid a higher price for you to have that privilege [Avery, Penguin Random House].

This year was one in which, if you live in a food-centric urban area, the pleasure of dining was replaced by concern for the many restaurants that were decimated by the pandemic. For this reason, the 2020 anthology of Best American Food Writing, is somewhat of a historic document, describing a food culture that will likely be forever changed. Editor J. Kenji López-Alt references the pandemic in his forward (the book was published in November), but all the stories in this volume were first published in 2019 and selected in February, just before the coronavirus stopped the world. Both a travelogue and a cultural guide, this year’s edition presciently touched upon some issues that would become themes this year: how to save the neighborhood grocery, behind-the-scenes hardships of the restaurant kitchen, white supremacy in Yelp reviews. In a new world where we more frequently ask about food authenticity, our complicity in obtaining it and our true need, some of the stories seem like light fare. But López-Alt, a chef and author of the James Beard Award–nominated column “The Food Lab,” fairly notes that stories likes these are important connections to history, culture and each other [Mariner Books, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt].

The World’s Best Champagne—According To The Experts

This New Year’s Eve, Support Restaurants And Bars

Wines For Roasting 2020 And Toasting 2021

Anyone who has traveled ancient routes, or dreamed of doing so, will find deep satisfaction in Cumin, Camels and Caravans: A Spice Odyssey by Gary Paul Nabhan. Published in 2014, this was an enjoyable, albeit academically hefty, book in a year of no travel, and when I looked to the past to escape the present. A prolific food-activism author, Nabhan has a long list of credentials that sum up everything we should concern ourselves with: he’s, a PhD agricultural ecologist, ethnobotanist, ecumenical Franciscan brother, and a pioneer in the heirloom-seed preservation movement (and he’s the recipient of a MacArthur “Genius Grant” fellowship, so there’s that). The author’s odyssey meanders along four historic trade routes: silk, frankincense, spice, and the Camino Real, the latter established between the Spanish missions and the U.S. for goods such as chilis and chocolate. His “travels” describe the origins of spices, where and how they were traded and culturally appropriated (the inset on saffron will resonate with most eaters/cooks), further summarized in the final chapter on cultural imperialism, reminding us that we are all complicit in our food choices [University of California Press].

My year-end guilty pleasure was the new James Beard biography, The Man Who ate Too Much by John Birdsall, a former chef and himself a James Beard Award-winning author. The first such book in a couple of decades describes Beard’s upbringing as a child and the migration from his childhood home in Oregon to New York City, via European capitals and an aborted theatrical career. Birdsall details, for the first time, chunks from Beard’s childhood—a boy who knew from age 7 he preferred his same sex, and whose appetite was indulged early on, no doubt contributing to his face being “as plump and pale as milk-poached meringue.” These are unusual glimpses, since not much of Beard’s personal archives survives. But Birdsall creates a substantial narrative from what is known: Beard’s ejection from college for sexual acts with a professor, the travels abroad that would inform his food perspectives, and his eventual migration to New York City, where he established his supper club, career and a new American cuisine. The biographer pierces into the dichotomy between the chef’s outer and inner selves—an outsized (6’3” and 300 pounds) and Falstaffian personality hiding his conflicted reckonings with his sexuality, and struggles with his appearance, finances, loneliness and depression. It’s little surprise to learn that Beard substituted food for unresolved emotional issues, but nonetheless, it hits home and reminds us how the yearning for food is primal, aching and, in the end, can be empty [W.W. Norton].

Published at Thu, 31 Dec 2020 21:45:58 +0000

Comments

Loading…