COLUMN: A Father’s Day promise to a broken dad

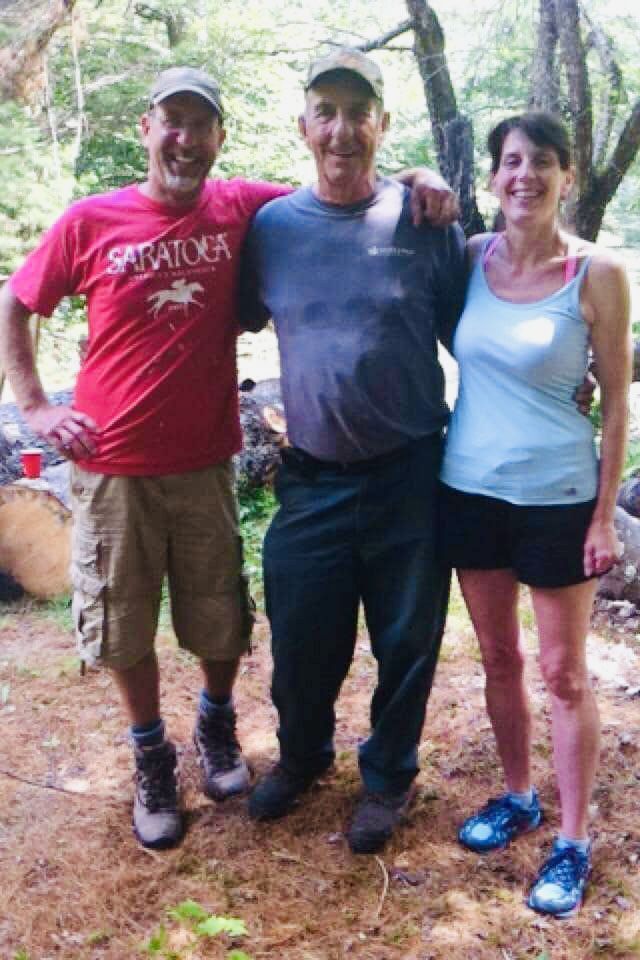

David Blow, left, poses with his father, Richard, and sister, Debbie, at the family’s camp property in Tinmouth, Vermont, after a day of milling lumber several years ago.

This isn’t really a happy Father’s Day for me.

Yes, I’m blessed with two super cool kids who have achieved a lot and make me extremely proud to be their dad, but my thoughts are elsewhere this holiday.

About five weeks ago, my almost 80-year-old mom packed a lunch for my almost 81-year-old dad — like she has for six decades — and he headed off to mow our camp property in rural Tinmouth, Vermont.

My dad retired as a contractor over 20 years ago after a heart attack, and mowing fields, trimming trees, cutting firewood and burning brush at the 300-acre camp property has been the new job that keeps him alive, in shape and sane.

But on that day five weeks ago, he made it only about a quarter-mile down the road when a “gray car” came up over a blind rise on his side of the road and he swerved to miss it.

The swerve led him into a ditch where he struck a rock that severed his front right tire and sent his Tacoma pickup airborne back into the road resting on his driver’s side.

Somehow, despite a fractures in his face, ribs and back — including a lower back compression fracture that splintered into 17 pieces — he pushed the passenger door open with his head and pulled himself out.

Later at Rutland Regional Medical Center, they realized he had bleeding from his brain and he was transferred to Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center.

My mother, sister and I were there when the ambulance arrived with him, though due to COVID regulations and his condition, only my mom could see him.

He survived the night, despite a scary bout of vomiting that had us really worried about the extent of his head injury.

But he was a very broken man.

The back pain over the next handful of days was so bad he didn’t even feel the facial and rib fractures.

Then came the eight-hour back surgery — and relief!

The pain subsided and now he could feel his other injuries, which oddly seemed like progress.

But there clearly was nerve damage, because despite the pain relief, his left leg didn’t work like the right one when they started having him walk.

And he fell.

Tests reportedly revealed no additional damage, but the pain started again — shooting pain that he said travels across his mid-section and down both legs, but especially bad on the left side.

He was then transferred to a rehab facility in Rutland, where he has fallen a few more times. The left leg just gives out and he has no idea when it will happen. His brain is working fine, thankfully, but he really doesn’t seem to be making a ton of progress walking.

He talks to me about “not making it out of here,” though we assure him he will.

He reminisces about lost brothers and sisters, and his long-deceased mom and dad.

This powerful, proud man with lumberjack hands and a work ethic I’m proud to have had instilled in me, has been reduced to a bed for over a month.

He talks about never having been in a bed that long, almost with shame. He talks about all the work he’s not doing.

When I visited on Thursday, he was like a caged rat, venting about getting home and how he’s sure he can navigate the house with a walker or wheelchair. He wants out and we feel guilty that he’s there, yet fearful of his exit.

My dad doesn’t really have hobbies, doesn’t read and doesn’t love TV, so he either sits in the recliner or lies in bed festering and dwelling about his diminished state and certain demise.

I bring him coffee and doughnuts and candy because he doesn’t love the facility’s food and he’s losing weight. I show him pictures of projects I’m doing and of my manicured property because they make him happy and proud and are such a contrast to my uncaring youth.

I had my oldest daughter record a song for him (he loves her version of “Somewhere Over the Rainbow”) and we were both teary when it ended on my phone.

He feels helpless.

I feel equally helpless to help him.

On this Father’s Day, I’ll be traveling to the rehab facility with family members to wheel him outside for cake and ice cream. I’m sure I’ll get him to laugh, despite the agony of his situation. And we will assure him that a plan is under way to spring him from rehab and get him home.

He fears not making it home, but that isn’t happening.

As a 54-year-old man, I’m so thankful to still have my dad. I can still ask him questions about building projects and home repairs and I know he relishes being able to offer his wisdom.

I teach students who are under 20 and have lost a parent. One, when I called him in to talk about his sagging performance, told me of having to care for his dying father who was riddled with cancer. He said he was the one his dad would call for when he needed help. I can’t imagine that burden as a teen.

With that perspective, I feel blessed to still have my dad as the patriarch of the family. But seeing him wither away in this facility is awful and will not be how his story ends.

That’s a promise to him.

David Blow is a freelance journalist and professor of Media and Communication at Castleton University. He may be reached at davent67@gmail.com.

Published at Sat, 19 Jun 2021 17:00:00 +0000

Comments

Loading…